Price of a diploma: Class of 2012 faces tough job market, rising costs, and increasing debt

There was a great article in Monday’s Wall Street Journal that discussed the tough job market the Class of 2012 is facing. Many of these new graduates will be competing with the graduating classes of 2011 and 2010 just to get on the bottom rungs of the career ladder. While it’s well-documented that graduating into a depressed labor market lowers lifetime earnings potential on average, today’s young graduates have additional hurdles to worry about: rising higher education costs and crippling student debt.

At EPI, we, with economist Heidi Shierholz, recently released an analysis of the labor market for recent high school and college graduates. The results are predictably grim, with unemployment rates for both sets of graduates spiking at the beginning of the Great Recession and falling very slowly in the recovery.

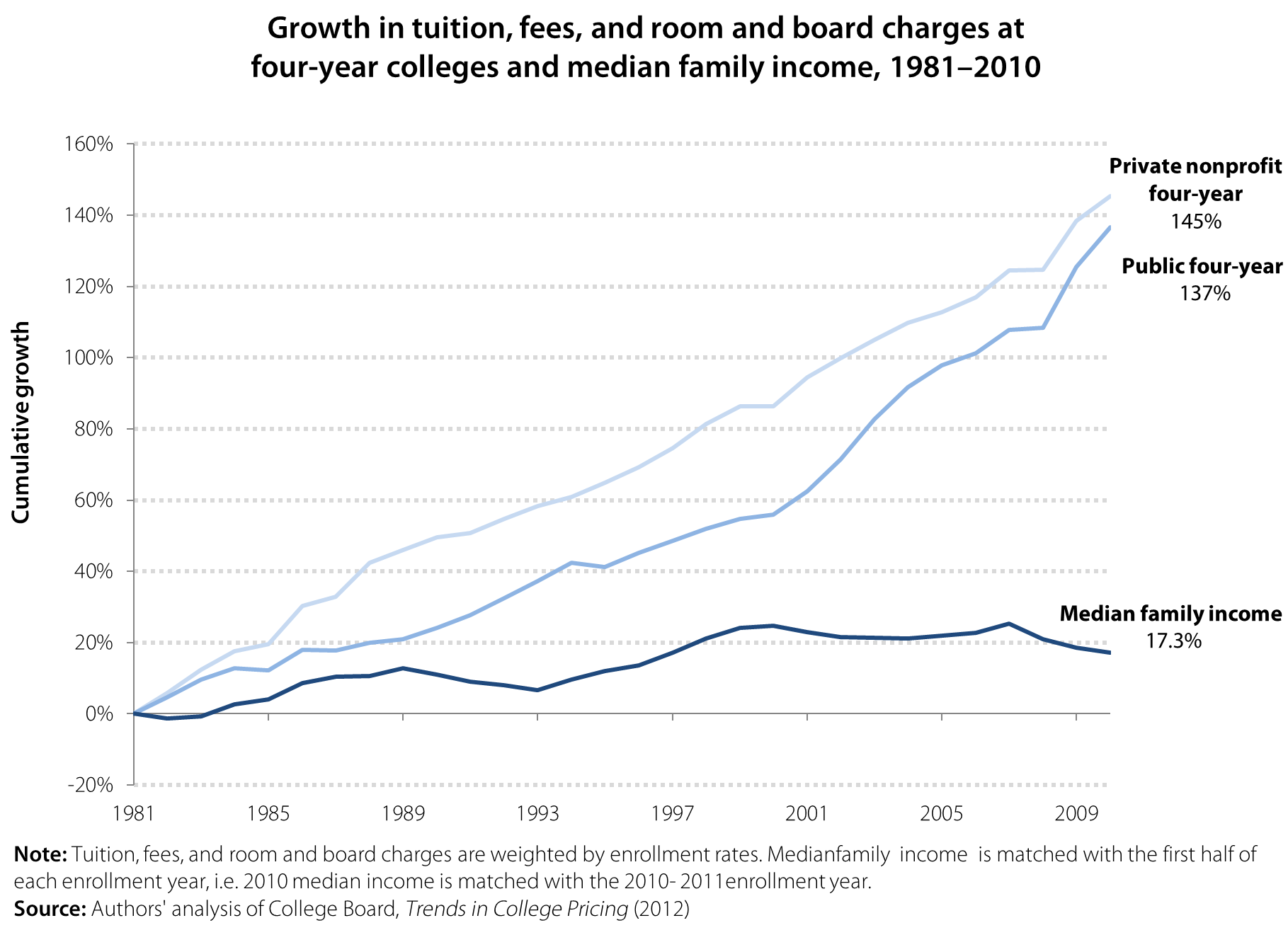

The report also highlighted the rising cost of obtaining a college degree. The figure below shows that the cost of higher education has been rising faster than family incomes for decades, making it harder for families to pay for college. From the 1981–82 enrollment year to the 2010–11 enrollment year, the cost of a four-year education increased 145 percent for private school and 137 percent for public school. Median family income only increased 17.3 percent from 1981–2010, far below the increases in the cost of education, leaving families and students unable to pay for most colleges and universities in full.

Unsurprisingly, a large majority of students and recent graduates take on debt to pay for college. Two-thirds of recent college graduates have student loans, and trends indicate that the number of student loans is increasing. Between 1993 and 2008, average student debt for graduating seniors increased 68 percent, from $14,410 to $24,238. Average debt for graduating seniors at public universities was $21,105 in 2008, and average debt for graduating seniors at private non-profit universities was $28,888 (authors’ analysis of Project on Student Debt 2010). In taking on these loans, students are taking a risk and hoping that they will be able to quickly secure work to begin paying them off after graduation. In recent years, and through no fault of their own, a growing number of graduates have been on the wrong side of this risk, with harsh consequences. Although most student loans have a grace period of six months before repayment begins, recent graduates who do not find a stable source of income may be forced to postpone payment though deferment or forbearance, miss a payment, or worst of all, default altogether on their loans. Deferment and forbearance are short-term fixes, however, and ultimately increase the amount borrowers owe once each period ends. Missed payments and default can ruin young workers’ credit scores and set them back years when it comes to saving for a house or a car.

Even worse, these young workers do not have a strong safety net on which to rely during the volatile job-seeking process.

Young workers are often ineligible for unemployment insurance, for example, because they must first meet state wage and work minimums during an established reference period—a reference period during which they are often in school and not working. Many new graduates are likely turn to their families for assistance. In 2011, 54.6 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds were living with their parents, an increase of 3.4 percentage points since 2007. This option is not, obviously, available to all young graduates. In short, young workers are being squeezed from multiple angles and their plight constitutes yet another instance of how damaging our tolerance of an underperforming economy truly is.

Additional findings and more analysis on the labor market facing young high school and college graduates can be found in our report, The Class of 2012: Labor market for young graduates remains grim.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.